Perimenopause: A very short history

- Nicole McGann

- Jan 13

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 26

Hippocrates & Hysteria Menopause, the “cessation of menses,” was recognized in medical texts as far back as Hippocrates. Its symptoms and the transition leading up to it, weren’t recognized until the 1930’s. Women suffering from mental, emotional, or physical symptoms were diagnosed with “Nervous Disorders,” “Moral Weakness,” or “Hysteria.” (1)

In 1821, a doctor in France coined the term “ménopause” and described it as an “event” (not a transition or phase of life). That was all the authority anyone needed. The word, and its description, were reprinted in British gynecology texts and American medical journals. (2) (3)

Over the next 100 years, medical professionals refer to menopause as a “period of emotional instability,” and a “risk factor for hysteria, insanity, or moral decline.” Eventually, the term menopause starts showing up in popular advice books, sermons, and etiquette guides. (1)(4)

Finally, Science.

In 1929, research was published showing that estrogen could be isolated and measured. Menopause was reframed as a biochemical change, and had nothing to do with morals or a woman’s sanity. (5)(6)

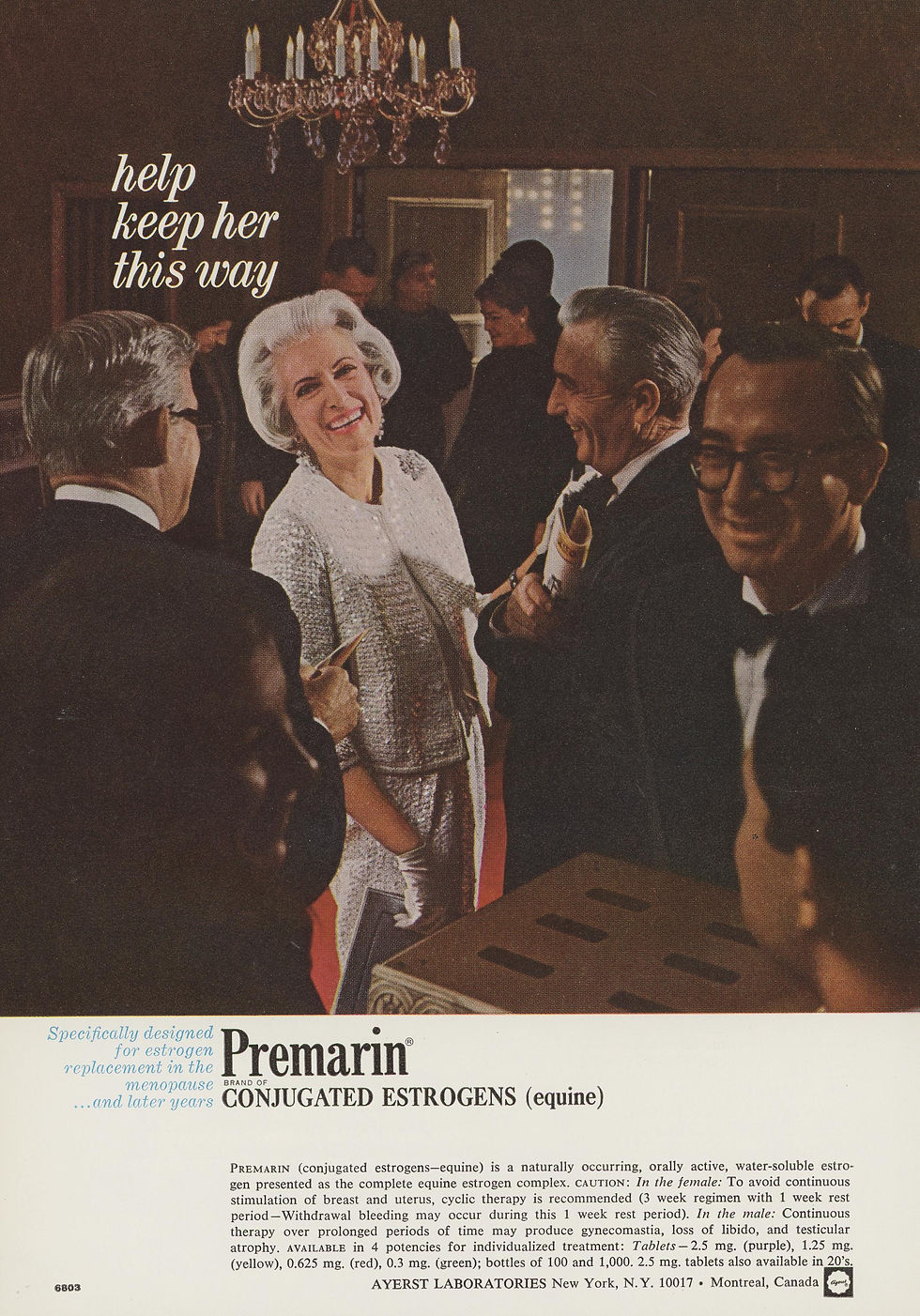

Now isolated, estrogen could be synthesized and mass produced. (7) Over the next decade, estrogen became routinely prescribed for “estrogen deficiency” to treat hot flashes, “nervous symptoms,” and “menstrual disorders,” (8) and by the 1960’s it’s being marketed as a “youth preserver.”

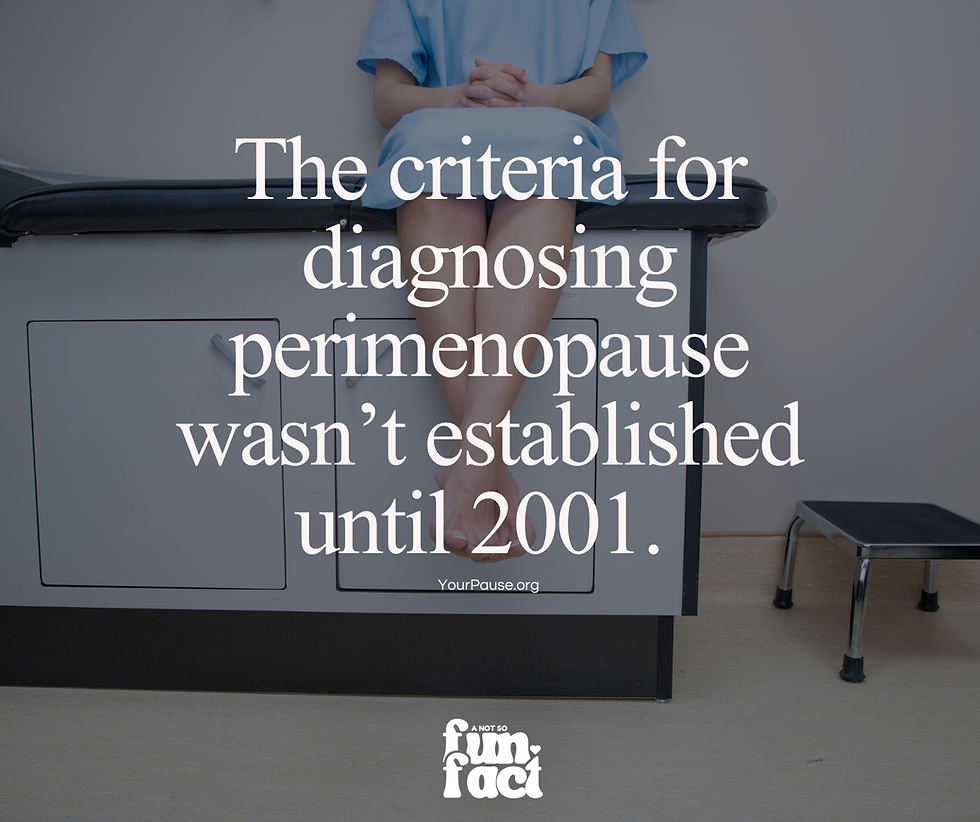

Over the next decade, clinicians and researchers start using terms like “menopausal transition,” and “pre-menopause.” (9) The word “perimenopause” didn’t appear in a single text and become adopted, like menopause. It was brought into use, over decades, by researchers and clinicians, around the world – but without any formal definition or way to diagnose it – until 2001.

“A select group of investigators attended a structured workshop, the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW), at Park City, Utah, USA, in July 2001, which addressed the need in women for a staging system as well as the confusing nomenclature for the reproductive years.” (10)

The participants were a multidisciplinary group of international experts in fields such as Reproductive endocrinology, Gynecology, Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Population health.

STRAW established:

•A lifespan continuum of reproductive aging

•Perimenopause (menopausal transition) as a defined stage

•Menstrual cycle patterns, not hormone levels, as the most reliable clinical markers

(Hormone levels fluctuate too widely during perimenopause to be diagnostic.)

STRAW noted:

There is no set age for when perimenopause starts.

“Women do not begin reproductive function (puberty) nor end it (menopause) at a particular chronological age.”

There is no set linear timeline to perimenopause.

“While most normal women will progress from one stage to the next, there will be individuals who ‘see-saw’ back and forth between stages or skip a stage altogether.”

Early perimenopause can be diagnosed based on menstrual cycle length. “A woman’s menstrual cycles remain regular in Stage −2 (early menopausal transition), but the length changes by 7days or more (for example, her regular cycles are now every 24 instead of 31 days).”

Late perimenopause can be diagnosed is based on two or more skipped periods. “Stage −1 (late menopausal transition) is characterized by two or more skipped menstrual cycles and at least one menstrual interval of 60 days or more.”

Symptoms are vary widely. “Not all women have symptoms as they transition to the menopause, and women with symptoms experience them in different combinations and with different levels of intensity.”

The STRAW framework is still the foundation of modern perimenopause science. (10)

Another decade of research led to updated guidelines in 2012. (11) STRAW+10 added: •Better characterization of early vs late perimenopause •Reinforced that FSH and estradiol levels are unreliable •Symptoms and cycle patterns matter most for diagnosis

In 2015, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence published its first menopause guideline and officially recognizes perimenopause as a “symptomatic clinical phase,” and advises against routine hormone testing in women over 45. (12) This is policy-level rejection of hormone testing for diagnosis! “Do not use laboratory tests to diagnose perimenopause or menopause in women aged over 45 years.” (12)

Not only was hormone testing not recommended for diagnosing perimenopause, starting in 2020 it was explicitly discouraged. Multiple reviews and papers explicitly discouraged hormone testing for perimenopause. Calling out that “labs can mislead clinicians and delay care.” Reiterating, yet again, that hormone testing is not required and not useful in diagnosing perimenopause. (13)

“Laboratory testing is often used despite the lack of evidence supporting its diagnostic value during the menopausal transition.” (13)

So here’s what I don’t understand – if scientists, policy-makers, and educators recognize that perimenopause is a transitional phase with treatable symptoms that should be diagnosed based on a woman’s cycle length and regularity. WHY ARE DOCTORS STILL TESTING HORMONE LEVELS AND TELLING WOMEN THAT THEIR “NUMBERS ARE NORMAL” AND THEY’RE TOO YOUNG TO BE PERIMENOPAUSAL!?!?

Let’s put an end to this shall we?

Step 1: Make sure you’re tracking your periods. (You can use one of these trackers.)

Step 2: Print out this PDF of cited research and guidelines to take with you to your doctors appointment

Step 3: If your periods meet the diagnostic criteria, remember, testing your hormones to see if they’re within “normal” range is not necessary for perimenopause diagnosis and treatment!

Sources: 1. Shorter E. Women’s Bodies: A Social History of Women’s Encounter with Health, Ill-Health, and Medicine. Routledge; 1982. 2. Gardanne C-P-L. De la ménopause, ou de l’âge critique des femmes. Paris; 1821.(Original coinage of the term) 3. Stolberg M. “Menopause in the eighteenth century.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 2000;74(3):477–501.

4.The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830–1980 Showalter E. Pantheon Books; 1985. 5. Butenandt A. “Über die chemische Untersuchung der Sexualhormone.” Zeitschrift für Angewandte Chemie. 1929. 6. Doisy EA et al. “The isolation of estrone.” Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1929. 7.Beyond the Natural Body: An Archaeology of Sex Hormones Oudshoorn N. Routledge; 1994. 8. Bell SE. DES Daughters: Embodied Knowledge and the Transformation of Women’s Health Politics. Temple University Press; 2009. 9. McKinlay SM et al. “The normal menopause transition.” Maturitas. 1992. 10. Soules MR et al. “Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW).” Fertility and Sterility. 2001. 11. “Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW).” Fertility and Sterility. 2001;76(5):874–878. 12. NICE. Menopause: diagnosis and management. NG23. 2015 (updated 2019). 13. Kling JM, et al. “Menopause management knowledge gaps among physicians.” Menopause. 2019;26(7):683–688.

Comments